Exploring L1 Data Availability Techniques in ZK Rollups

Introduction to ZK rollups and Data Availability

Rollups inherit the security of the Ethereum base layer by making sure that transaction data is available on L1. This increases censorship resistance for L2s even if all L2 nodes are ceased or stop working. The underlying data availability differentiates ZK rollups from other L2 scaling approaches such as independent sidechains (Polygon PoS) or validiums.

Within the architecture of ZK rollups, a lot of focus lies on the prover of the L2 network, while other characteristics such as L1 data availability are often widely overlooked.

ZK rollups not only achieve scalability by off-loading transaction computations off-chain, but also allow to utilize various compression techniques for storing on L1. As Vitalik Buterin explains, parts of the transaction, which are only used for verification but not for computation of state updates itself, don’t need to be accessible on L1 (e.g. signature data). This leaves a lot of room for optimization for L2 rollups to achieve higher scalability.

For this article, I have gathered information from official documentations of popular rollups and numerous Twitter discussions (particularly here and here) to present an overview of data availability approaches for ZK rollups. My aim is to provide a clearer understanding of the various approaches to data availability in rollups and their implications for the network. Popular ZK rollups include zkSync Era, Starknet, Polygon zkEVM, and Scroll. The first three are the most popular universal ZK rollups deployed on mainnet based on TVL on L2Beat in July 2023. Although Scroll is not yet deployed, it is highly anticipated by the community and is currently only available on the testnet. Other notable mentions for upcoming ZK rollups include Taiko and Mantle.

How does Data Availability work in Rollups?

There are two different approaches to data availability: State diffs and Full transaction history. For state diffs, only the storage changes of a transactions are stored in the L1 contract. With state diff data, we cannot distinguish if Bob sent 10 ETH to Alice within a single transaction or within ten separate transactions. Large transactions with small state changes as well as high-frequency transactions such as oracle price changes can save a lot of gas using the state diff approach. The rollup contract only knows about the state aggregations of a sequenced transaction batch, but not about the individual transactions.

It is also possible to store the complete transaction history of a rollup batch on L1. While this goes along with higher gas costs per transaction at the moment, it also increases transparency. Without any further compression, Ethereum L1 needs to store larger amount of data than usual due to the higher transaction throughput of the rollups. With the transaction history, the rollup contract can order and execute all transactions. State diffs along with a validity proof allow us to verify the resulting state and the integrity of the computations, but with transaction history we can investigate the L2 transaction history can follow precisely how the end state was achieved, without relying on L2 node data.

zkSync Era and Starknet (which are arguably also more closed-source in comparison to the other two competitors) utilize state diffs, while Polygon zkEVM and Scroll store the whole transaction history.

A quantitative comparison between zkSync Era and Polygon zkEVM

Let’s look at an example and compare Starknet and Polygon zkEVM to see the different data availability techniques in practice. We will compare the gas costs of committing a batch on L1 for both rollups. For this, we will look at the L1 contract of both rollups and decode the input data of the respective transactions. This way we can see how much data is stored on L1 for each transaction and calculate the average gas cost per transaction.

zkSync Era Committing Fees:

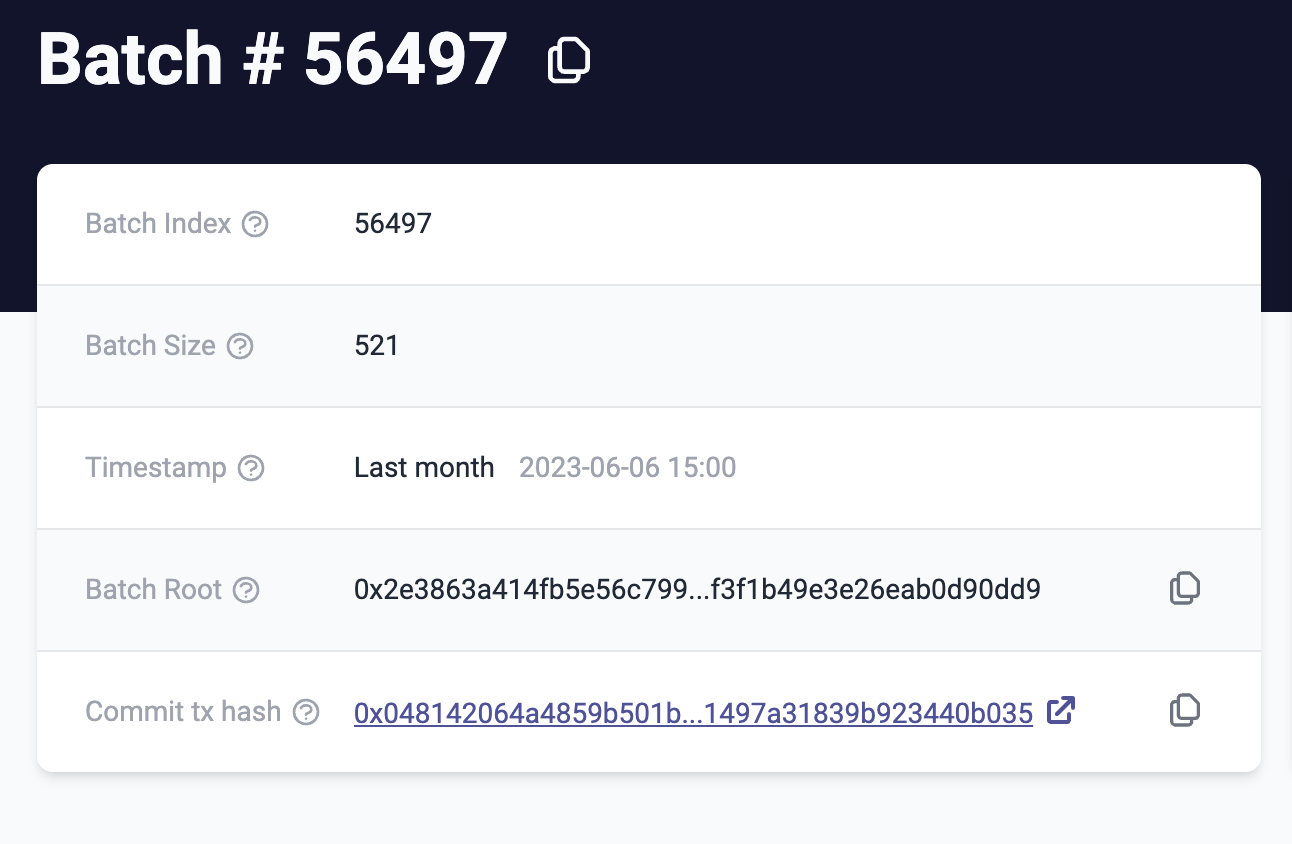

If we investigate the L1 Rollup Contract of zkSync Era, we can see two types of transactions: Committing and Proving Blocks. For our interest of data availability on L1, the commitment of the batch will be sufficient. We inspect and decode the input data of e.g. Batch 56497 and also compare it to the zkSync block explorer. This rollup batch has a size of 521 transactions and gas usage of 1,268,047, which results in 2433.87 gas/transaction for this batch on zkSync Era.

We repeat this process for five different batches to achieve a representative average (as a certain batch may contain artificial transactions for example). This way we get an average cost of 2263.53 Gas/Transaction for storing data with state diffs on zkSync Era. Details can be obtained from this Sheet.

Polygon zkEVM Committing Fees:

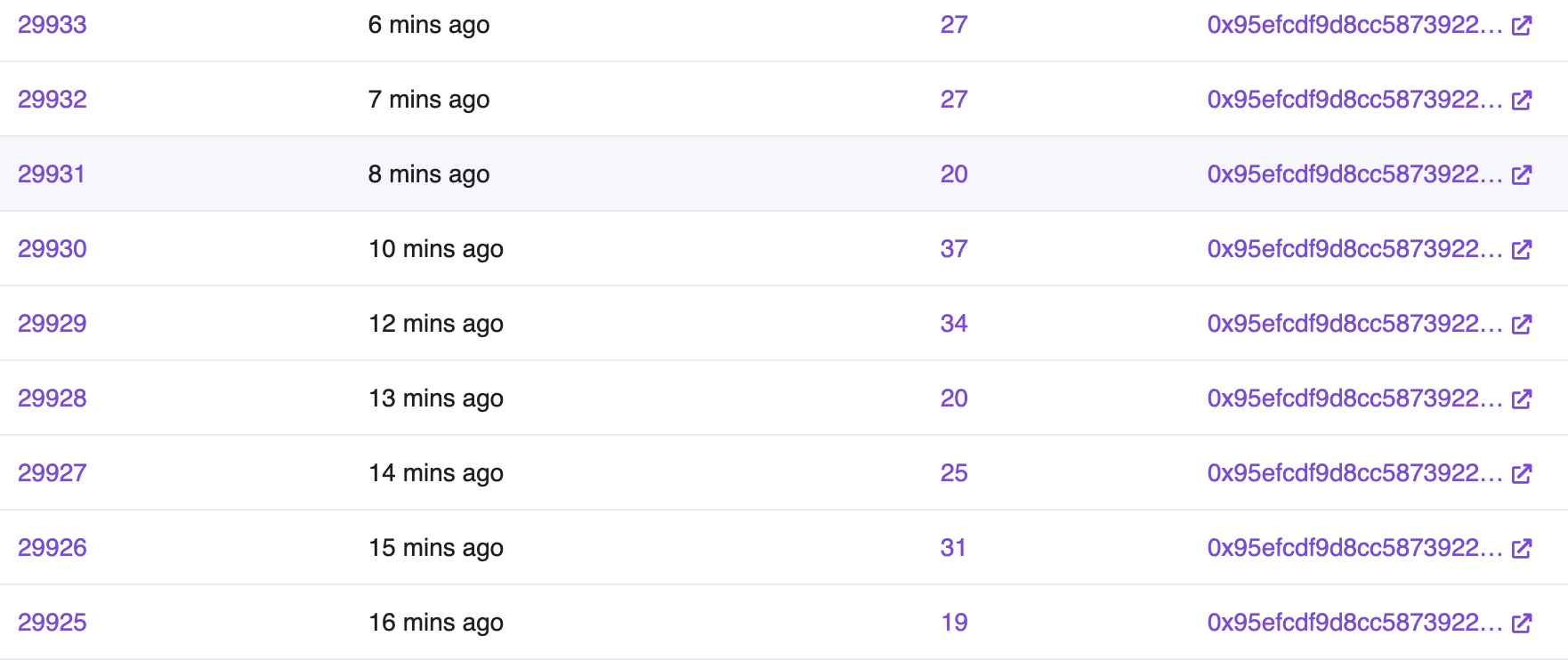

We do the same analysis for Polygon zkEVM, where we can see that ten batches including Batch 2933 are committed within the same sequencing transaction to commit data on the L1 contract. In total, there are 240 transactions in 10 sequenced batches.

The sequencing transaction has a gas cost of 1,406,602. When decoding the input data, we can find transaction data such as e.g. individual transaction hashes. For the described sequence, we get a gas cost of 5869/transaction which is much higher than zkSync Era.

As in the previous example, we repeat the process for different batches to get a more representative average gas cost per transaction and get an average committing cost of 5417.96 gas / transaction.

An interesting observation visible in the table is, that the variance of batch size and gas cost per transaction is much higher for transaction-based Polygon zkEVM over state diff based zkSync Era.

The previous examples were helpful to see the differences of state diffs and full transaction history in practice on Mainnet. We were even able to decode some of the transaction data for the Polygon zkEVM batches. As expected, full transaction history comes with a higher gas cost per transaction at the moment. Still, this is by no means a complete evaluation yet to prefer one rollup over the other. It is just a comparison for the costs of data availability on L1 for different kinds of rollups. Also, it is important to remember that there are still many artificial transactions in the sequenced batches. To get a detailed comparison we would need to store the exact same transactions in the respective rollup and compare again.

State Diffs vs Full Transaction History

As mentioned before, an advantage of state diffs is that they can optimize for high frequency transactions like oracle updates and DeFi transactions. However, something that should be kept in mind is, that “large” transactions (with lengthy input calldata) can have “small” updates on state, but “small” transactions can also have “large” state updates. This implies that different approaches to data availability can lead to varying optimization of gas costs for different smart contract functions.

However, transaction fees are not the only thing that matters. Another aspect is transaction finality. Here, the transaction history approach has an advantage as they achieve faster L2 finality. L2 finality means the data has been executed and sequenced on L2. For L1 finality, one still has to wait for the validity proof. With transaction history e.g. on Polygon zkEVM, transactions are sequenced roughly every 10 minutes, while state diff based ZK rollups only achieve finality once the validity proof is stored on L1 together with the validity proof

Storing complete L2 calldata on L1 can still undergo various optimizations, e.g. as proposed by EIP-4488 or by excluding transaction signatures (the tied validity proof is sufficient to provide the integrity of the transactions)

Saving the rollup batches through the transaction history also allows to develop applications such as a rollup block explorer solely based on verified L1 data, while ZK rollups’ state diffs alone may not be sufficient to achieve this and also have to incorporate data from e.g. L2 full nodes which are highly centralized and trusted at the moment.

An advantage of posting transaction history is that you can self-sequence transactions without the need for a decentralized sequencer. While zkSync and Starknet do not offer forced transaction inclusion yet, Polygon zkEVM has an implementation in the smart contract, which theoretically allows to force transaction inclusion in the event of a sequencer failure by sending them to L1. However, this functionality is still disabled in the contract at the moment.

Conclusion

All in all, while the number of arguments to store transaction history may be higher here, this does not necessarily imply a strict advantage of transaction history based ZK rollups over state diff based ones. In the near future, we can expect much lower fees with state diffs and this is ultimately the main goal of a rollup in order to achieve scalability. Starknet and zkSync Era have already demonstrated that state diffs work in practice on mainnet. In the long term, a combination of both approaches may incorporate the advantages of both. As Patrick McCorry suggests, there is still “a low hanging fruit piece of research”, to determine which types of transactions and applications benefit more from either approach. Personally, I am curious how L1 data is used exactly to generate a validity proof and how the two approaches make a difference here. Overall, the lack of documentation and open questions show, that the focus of all four presented rollups has been lying on prover performance so far, while there are also still numerous opportunities to optimize in different areas.