A quick prover analysis for a ZK-EVM-based rollup

ZK-EVMs have gained a lot of attention since Polygon, Matter Labs, and Scroll announced their ZK Rollups during EthCC 2022 in Paris. ZK-EVM-based rollups use zero-knowledge proof technology to generate generate a validity proof for the operations of Ethereum transactions on the EVM.

While the concepts of different rollups are not too hard to understand, the available information is surrounded by marketing language, as the different teams want to attract developers and users to their ecosystem to gain an early market share. This makes it hard for technically-versed users or researchers to understand, what’s really happening under the hood.

A goal of my recently finished master thesis was, to investigate, what rollups really mean, when they claim to be the most “developer friendly”, the most “Ethereum aligned”, or “the fastest”.

Vitalik Buterin already helped a lot by classifying different ZK rollups into different levels of Ethereum compatibility. Also, the L2Beat team is constantly pushing for more transparency to uncover any security issues in the rollup ecosystem. A part of my thesis was to test the performance of the ZK prover, which is computing the validity proof for different transactions. The following paragraphs describe experiments and their take-aways performed on a private deployment of the Polygon zkEVM running on own hardware.

Our experiments on the Polygon zkEVM Prover were designed to investigate the impact of different hardware, transaction types and proving batch sizes

Concretely, we adapted:

- Provided Hardware (700GiB RAM, 32 and 64 vCPU Cores)

- Transaction Type (ETH transfers and ERC20 transfers)

- Batch Size (1, 10, 100, 500)

and measure

- Proof Generation Time

- Proof Size

- Resource Consumption (Memory and CPU)

Naively, one may expect that more load on the prover will result in worse performance, i.e. more complex transactions such as smart contract calls will increase proof generation time. Also, a larger batch size (more transactions to prove) would lead to a larger proof size.

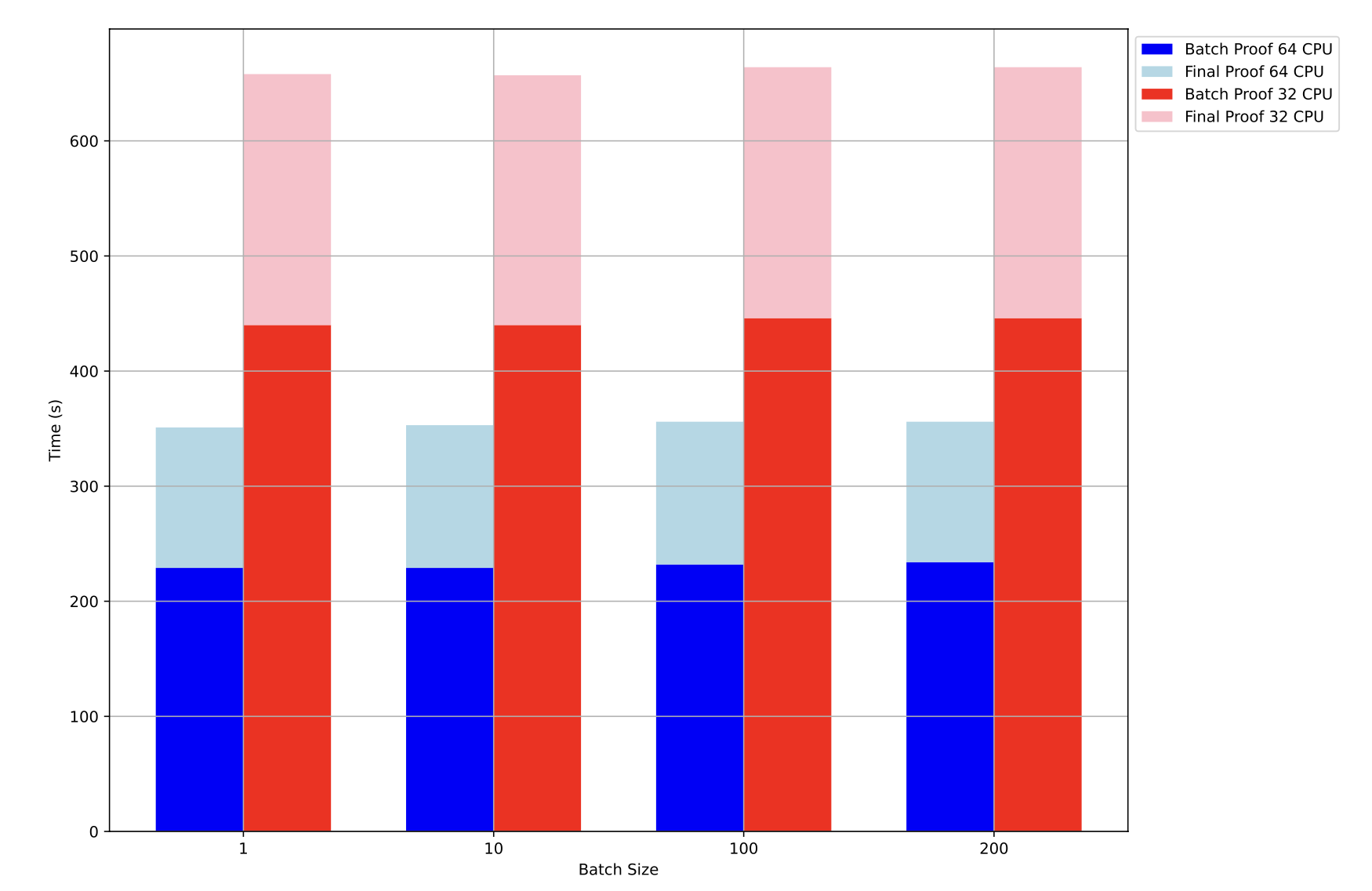

The results for standard ETH transfers are visualized below and show the following:

- With 64 CPU cores, a finalized proof is generated in roughly 350s

- With 32 CPU cores, a finalized proof is generated in roughly 650s

- An increases batch size does not alter prover performance

Initially a surprise, an increased batch size did not directly lead to a worse proof generation time. A second experiment using ERC20 transfers also did not alter proof generation time. Proof sizes also remained constant with 2.1MB for a STARK batch proof and 2.5KB (840 times smaller) for the final SNARK proof.

In a third experiment, we measured proof aggregation time to be around 15s on our 64 CPU node. Proof aggregation allows to forge an aggregated proof of multiple batch proofs, which can be computed in parallel.

All in all, our experiments lead to the following take-aways.

-

Proof generation time is not affected by batch size or transaction type.

This is due to the maximum capacity of the execution trace matrix being a limiting factor, with a fixed maximum step counter at . The prover might not be optimized for batch proofs that don't fully utilize the trace matrix. Since the executor uses a predetermined matrix shape for all proofs, the polynomial constraints also have a fixed degree. This means that even proofs not fully utilizing the trace matrix still generate a proof over the entire matrix, leading to unchanged prover performance. This aspect could soon be improved by developing proof systems with dynamic execution trace matrices that vary for different batches. Polygon has termed such optimizations as variable degree composite proofs (VADCOPs). VADCOPs enable state machines of varying sizes to generate proofs and compose them together.

-

Vertical scaling is possible.

While memory usage is constant around 500GiB, an increase in CPU power leads to increased prover performance. This behavior is expected to continue for even more CPU cores. Within ZKP generation multi-scalar multiplications (MSMs) and fast Fourier transformations (FFTs) are heavily used and computationally expensive. To tackle this bottleneck, they can be heavily parallelized and optimized with specialized hardware. GPUs, ASICs and in particular FPGAs are expected to significantly improve prover performance.

-

Horizontal scaling is possible.

Fast proof aggregation allows to compute multiple proofs in parallel and can therefore greatly improve the throughput of a rollup. In a future blog article, we may provide a quantitative assessment of how large the throughput can get with proof aggregation.

-

Sequence then prove allows for fast finality.

It would be wasteful to compute a batch proof for batch that doesn’t exhaust the complete execution trace, as the compute costs will be the same. Fast finality can still be achieved as the sequencer publishes transaction data on-chain on the Ethereum base layer. Still, it may take a longer time until the prover computes a proof.

All in all, while ZK rollups have improved vastly in the past year, but particularly innovation in the area of hardware acceleration and multi-provers (Scroll making first steps with TEE proofs) will change the current landscape and greatly improve performance and security.